- Home

- Steven DeBonis

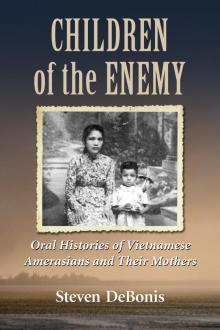

Children of the Enemy Page 7

Children of the Enemy Read online

Page 7

So when the security guards come to neighborhood nine, the witnesses say that Tuan Den and Raymond were there. So security comes to my billet and they say, “Raymond, the eyewitness say they saw you there.” I say, “Yeah, I was there, because it’s my patrol.” Because my job is the Inter-Neighborhood Patrol. They say, “Someone says you stabbed him.” I say, “No.” They say, “Someone says you beat him with a guitar.” I say, “No.” I’m not stupid, to say that I did that. So Tuan Den says, “I stabbed him because he was tryin’ to stab me. I’m not goin’ wait for him to hurt me. He threatened me, so I gotta get him first.” So, they bring Tuan Den to the monkey house.

I have a friend, he works here. He is a Vietnamese, but he is a Filipino citizen. He tells me, “Raymond, I heard security say they gonna get you.” And I say, “Get me for what?” He tells me, “Because you involved, and they don’t like you.” You know, one time I complained to Mr. Deles, their boss, about how security mistreats the Amerasians, and he disciplined them. So security don’t like me at all.

I read the statement Duc give after they brought him back from the hospital. It’s very clear and accurate, but Duc didn’t recognize me, didn’t even identify me. He only identified Tuan Den as the one who stabbed him, but then security talked to him and gave him some reason to hook me into the case. Duc’s companions, they don’t like Charlie, they don’t like me, they don’t like Tuan Den. They gave statements, and the police came and arrested us all, even Charlie and Minh.

We spent five months in the Filipino prison in Balanga. Finally, I think my [American] friend who I work with, he convinced Duc to drop the charges, and they dismissed the case and let us out. But Tuan Den and I are still on hold. They not lettin’ us go to the States yet. I heard someone say that policies on refugees going to America are a little stricter now because many of the refugees comin’ through ODP committed crimes in the United States. The charge against me was frustrated murder [attempted homicide] , and even though it was dismissed, it affects, you know, my record. So all I can do is wait.

Tuan Den and Charlie

When I got back from Balanga, Mr. D. from JVA called me to his office and asked me if I ever heard anything about an MIA named Robinson T. Water, who applied to leave Vietnam as an Amerasian. I tell him that I never heard of that, but I gave him the photo and the piece of paper that the lady in Vietnam gave me, the photo of the black guy she said was being kept by the Montagnards.

So recently, Mr. J., from the U.S. Embassy, calls me to the office, and he asks me to sit down. He brings me the photo, and he asks me, “Raymond, can you recognize this person?” I say, “No sir, I cannot recognize the person, but I recognize the photo, because it is my photo. I gave it to Mr. D. before when he was working here with JVA. But this person, I have never seen him before in my life, I don’t know who he is.” Then Mr. J., he sort of looks at me, straight in my face, and he says, “Okay, you look over there,” and I see that he is trying to compare the photo with me. He says,

Tuan Den, Charlie and Raymond

“How old are you?” I say, “My documents say I’m twenty-six, but I don’t know exactly how old I am.” He asks me many questions, and he tells me to write down everything about the woman who gave me the photo.

So my case worker, Marivic, she says, “Raymond, the people been talkin’ about this thing. They think that you are the MIA.” I say, “How could it be? I’m not an MIA.” She say, “Yeah, but that’s what people think.” Of course I’m not an MIA. I learned English from living with black Americans on the base. I wish I was the MIA, then I could go to America.

I ask her, “When I’m gonna leave?” She says, “It’s not sure if the United States will reject you or not. If they don’t want you to go to America, what you gonna do?” I say, “My expectation is I want to get out of here and look for an opportunity to study, to help people. I can get my opportunity in America. If they reject me and send me back to Vietnam, no way. They should just kill me, that’s the easier way.”

The Vietnamese people have the prejudice that I am more American then Vietnamese. My custom, my culture, my accent is more American than Vietnamese, and they don’t like me at all. You think I will agree to go back? No. I would rather drink some medicine so I can die easy. No future, if I be sent back there, no future.

Postscript: Raymond left the PRPC for Hawaii in April 1992. His sponsor was John R., the American Vietnam veteran who had returned to Vietnam to set up the Amerasian programs.

Nguyen Thi Hong Hanh

“I grew up without love.”

Her ebony skin is from her American father, her high cheekbones and almond eyes from her Vietnamese mother. Hanh is in the refugee camp with her Vietnamese husband and their one-year-old daughter.

We are speaking on a clear, hot February day outside the Buddhist temple. Hanh speaks little English, and we converse through an interpreter.

I WAS BORN in Pleiku. I lived on Nguyen Ky Hoc Street, in a cement house, with my stepparents and their five Vietnamese children. When I was four years old, my mother left me. I have a picture of her, but I don’t remember her. I never knew where she went.

When my mother gave birth, she hired a baby-sitter to take care of me. She worked as a waitress at the American base in Pleiku. When I was four, my father returned to America, and my mother went away. She just left me with the baby-sitter became like my stepmother and didn’t come back, and that baby-sitter

Nguyen Thi Hong Hanh, in the PRPC, February 1992

My mother didn’t tell the baby-sitter that she was leaving. She just abandoned me there. The baby-sitter never told me anything about my mother, but the neighbors said that my mother got remarried and lived in Kon Turn. I never saw or heard from my mother again.

I never went to school in Vietnam, not even one day. I learned to read Vietnamese from some friends, mostly other Amerasians. Vietnamese didn’t let me be friends with their children. Some people wouldn’t even let me work for them. That’s what my stepmother told me. Black Amerasians have a lot of problems.

My stepparents treated me badly. When I was about six years old, they sent me out to work to make money for them. I took any job, like maid or baby-sitter. My stepparents were teachers, but they never sent me to school or taught me at home. They just made me work. They didn’t love me, I grew up without love.

Minh

“I rarely left the temple, so I know only a little about the life outside its confines.”

The Buddhist temple of neighborhood seven sits on a bluff overlooking a tranquil valley framed by the slopes of the Zambales range. The river below, barely a trickle in the dry season, brings life to acres of rice when swollen with monsoon rain. Refugees wander into the temple grounds to worship, to admire the statue of Quan Am, or merely to watch the river wind through the valley on its way to the South China sea, five kilometers distant.

Minh listens attentively as my interpreter introduces us. He is a fine-boned young man of twenty. His light skin and Western features mirror an unknown American father; his pensive demeanor bespeaks the teachings of the Buddha. Adopted by Buddhist nuns when still a toddler, Minh has lived in Buddhist temples for twenty years. His hair is cropped close to the scalp, and he wears the saffron robe and gray pants of a monk.

We sit with my interpreter on a concrete embankment outside the temple wall, sharing a tiny patch of shade. Chanting wafts through an open window, a feeble breeze teases wind chimes in a nearby tree, and the mid–February sun blazes in premonition of the approaching hot season. As we speak, the sun shifts. The spot of shadow we inhabit moves, and we follow it.

I WAS LEFT in an orphanage in Saigon, and so I know nothing of my real mother. When I was still an infant, maybe two or three, I was adopted by a Buddhist nun, and she took me to live in the Hue Lam temple at 130 Hong Vinh Street, in the 11th district of Ho Chi Minh City.

There were five Amerasian children adopted by the temple and brought up there and probably about twenty-five Vietnamese children. I rarely left the

temple, so I know only a little about the life outside its confines, and I did not experience the many problems of the Amerasians who lived outside of the temple.

Some of the orphans adopted by the temple went to school in the temple. Others went outside, if they wished. I studied only inside the temple. There were many things I wanted to learn about Buddhism and I became a monk. The Buddhist monk follows several rules. The Buddha doesn’t permit us to kill any animals. We cannot eat meat or fish, so I am a vegetarian. Monks can’t steal, rob, or do bad things. We cannot have sex, tell a lie, drink alcohol. We are told not to be talkative, to boast, exaggerate, or use foul language, and to take advantage of no one. I believe the most important rules are “Don’t kill any animal, and don’t take advantage of anyone else.” All monks and nuns must honor the teachings. I have grown up with these precepts, so it is not difficult for me.

Minh

Minh by the statue of Quan Am in the PRPC Buddhist temple.

Before 1975 the Hue Lam temple was for nuns only. There were only four nuns in the temple, no monks, and these nuns brought in many orphans to care for. The nun who adopted me took care of myself and one other child. There were many orphans there, maybe thirty. Of these children, some went to America, some left the temple and were drafted by the government into the military, and about five remained in the temple to become monks or nuns. When I reached seventeen, the local authorities no longer allowed the adopted boys to remain in Hue Lam temple. They said that since the temple was for nuns, all males must leave. Of course the nuns did not want their adopted children to leave, but we had no choice. We were forced to move to another temple, and I went to Vang Duc temple in Tu Duc, on the outskirts of Ho Chi Minh City. The local authorities often make difficulties for the monks. They don’t want them to continue their [religious] studies.

My life here in the PRPC is similar to Vietnam, I live in the temple. In Vietnam I studied, and here I study as well, but I’m studying English for the first time. The teacher teaches well, but I feel that I don’t have ability in learning it. I never studied any English in Vietnam, and it is very difficult.

I have no sponsor in America. I don’t know where I will go. I hope to improve my English there and to be a Buddhist monk, but I don’t wish to wear the robe. I left Vietnam in order to know different things and go to different places. I want to be part of society. I don’t want to hide in the temple. I would like to be active in the community. The robe is not important.

Tuan Den

“If I am attacked, I might not be able to be patient.”

Although it is not his real name, everyone calls him Tuan Den, roughly translatable as “black and smart.” Always well dressed and sporting a stud in his left ear, he is well known in the refugee camp by Vietnamese as well as Amer-asians, and certainly by the camp security. His size, his imposing demeanor, and his reputation for toughness all contribute to his notoriety.

At five feet, ten inches, slender but strong, he towers above most of his countrymen. With his height, his black skin and curly hair, there is little in Tuan Den’s appearance that suggests the country of his birth. As with so many Amerasians, it is the American side of his parentage that is most evident.

Shortly after arriving in the PRPC, Tuan Den spent five months in prison with three other Amerasians, charged with the stabbing of another refugee, a Vietnamese named Duc. The narratives of two of these Amerasians, Charlie and Raymond, also appear in this book. The details of the stabbing vary depending upon whose version you hear. Speaking through an interpreter, Tuan Den, though he is vague in his account, claims that he was simply defending himself from Duc’s knife attack and is not sure how Duc received his injury. Duc recovered and eventually dropped the charges of “frustrated murder,” the Filipino equivalent of attempted homicide. The Amerasians were then freed from prison.

Also in dispute is Tuan Den’s account of his stay in Dang Thao camp in Vietnam, a facility for youth who run afoul of the Communist government’s rules. Raymond, who was there at the same time, claims that Tuan Den, after being admitted as a prisoner, eventually became a much-feared guard. Tuan Den disputes this, claiming that he was just a common detainee.

The top two joints of Tuan Den’s left pinky are missing. This is not uncommon in Amerasian males and seems to be done for various reasons, generally to show courage or sincerity. This is what Tuan Den says about it: “I had a girlfriend in 1989. She was treating me bad, and I was suffering, so I chopped off my finger.” The implication is that he proved the depth of his love in this manner.

WHEN I WAS A CHILD, I did not live beside my mother. She was a bar girl, and when she went to work, she left me with a baby-sitter, an old, poor lady who made some money by watching people’s kids. One day my mother just dropped me off there and never came back, so it was that old lady who raised me. She never told me much about my mother, only what I just told you.

I suffered a lot because I was Amerasian. People embarrassed me, discriminated against me. Other children called me My lai and lai den [Amerasian and Black Amerasian]. I had no chance to go to school because I had no birth certificate.

When I was a teenager, I went out to live on the street and to earn some money. I was part of a group of kids, shining shoes and sleeping on the street. When we went out to work, we would go our own ways, but when night came, we would come back and stay together in one place.

I was the only Amerasian in the group. The others didn’t treat me as an equal, they stuck together. Sometimes when I came back, they would take my money, but there was nothing I could do because I was only one. If I separated from them, I could not work that area, where most of the business is. So I had no choice.

Eventually, I got into street crime. We cornered people at knifepoint, at night, in dark places. We’d tell them to give up their money. If they gave us the money, we’d let them go. If they resisted . . . [Tuan Den makes a stabbing motion with his arm.]

When we got the money, we had to give it to the gang leader, a Viet-namese about twenty years old. Even if I was the one who did the robbery, he would let me keep just a little of the money. I didn’t like that, but there was nothing I could do. I didn’t feel close to the people in the gang, but I needed them to survive. The life of crime didn’t bother me. I just thought of it as business.

Even though I am big and black, I never really worried about being identified by our victims, but somebody made a complaint, and the police came and picked me up. They sent me to Dang Thao prison, a camp for youth offenders on an island near Saigon.

When they told me they were sending me there, I didn’t know how bad it could be. It was terrible, the worst time of my life. We got up at six-thirty and worked till eleven-thirty. We’d get a little to eat and then go back to work until six, and go back to the barracks. We worked everyday, there were no holidays.

I had to do farm work, growing manioc, sweet potatoes, cutting grass. I was not familiar with the work, and when I made a mistake, they would scream at me, call me an animal, an American. I thought about escaping, until I saw what happened to people who tried to escape and were caught. They were beaten badly.

After three years, they released me, and I went back to Saigon. I got a job as a porter in a market, but after a month I left. I heard the people saying that the Amerasians could apply to leave the country, so I went out to the Amerasian Park and made the application to leave Vietnam and go to America.

I stayed in Amerasian Park, sleeping there and waiting for my name to be called. One day a woman came to me and showed me a picture. She said that the picture was of me as a baby and claimed she was my mother. I looked at the picture, but I was suspicious because she didn’t raise me. She said that she had been looking for me a very long time. Now that she met me, she said she wanted me to come home and live with her, but I said, “You didn’t take care of me when I was a child, so I don’t want to go with you now.” Many women come and try to tell Amerasians that they are their mothers, to try to go to America, so I was susp

icious about that, but she never asked me to take her to United States, and she never told me why she had abandoned me.

She came and visited me often. The last time I saw her she asked me to say hello to her friend in PRPC, and she wished me luck. I still don’t know if she was really my mother.

My happiest day in Vietnam was the day I got the ticket to leave, in June of 1990. I arrived in the PRPC on July 2, 1990. When I got here, I met many Amerasians who knew me in Vietnam. Most of the Amerasians here had been drinking and dropping pills, doing the bad things. I always advised them to stop. So, many people were saying that I am the Amerasian gang leader. That’s the reason why Duc, who is a troublemaker and a long-stayer here, gave the word to threaten me.

I went to neighborhood nine to visit my girlfriend. Duc lives down there. He saw me and he attacked me with a knife. He was drunk, and I defended myself. I pushed him, and he got hurt. It took place so fast that I don’t exactly know what happened [Duc was stabbed]. So they sent me to jail in Balanga for five months, and when Duc dropped his charges they sent me back here to the PRPC. I am still here on hold my departure for America has been delayed.

Children of the Enemy

Children of the Enemy