- Home

- Steven DeBonis

Children of the Enemy

Children of the Enemy Read online

The author between two of his Vietnamese and Amerasian students in the Philippine Refugee Processing Center.

Children of the Enemy

Oral Histories of Vietnamese Amerasians and Their Mothers

STEVEN DEBONIS

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0529-6

© 1995 Steven DeBonis. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

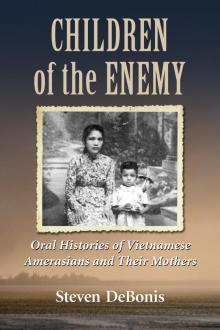

On the cover: Thuy at five years old with her mother (courtesy Nguyen Thi Ngoc Thuy); background dust storm (iStockphoto).

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

In memory of my grandfather, Irving May,

and for my grandmother, Sonia May,

and their great-grandson,

Noah David DeBonis

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My deepest appreciation goes to the Amerasians and their mothers, who despite the stress of refugee camp life, the sorrow of leaving friends and family behind in Vietnam, and the uncertainties of their futures in the United States, were kind enough to share their stories with me.

Mr. Khuyen D. Pham spent hours reviewing the narratives, explaining the arcane, ferreting out the implausible, and correcting my spelling of Vietnamese words. Our long discussions provided me historical and cultural perspectives on the personal accounts that appear in this book. Mr. Khuyen is an interpreter par excellence and assisted me in that capacity as well. He also contributed “Changes in Province and City Names in Vietnam after 1975,” which appears in the Appendix.

Tuan Anh Pham and Michelle Noullet patiently responded to my many letters and faxes, answering questions and providing information essential to the completion of this book.

A number of people acted as interpreters and cultural informants. Several of them have also contributed their own narratives to this text. Most were at the time refugees themselves, subject to the same demanding refugee camp schedule as the interviewees for whom they translated. In days filled with English study, mandatory community work, and waiting in line for scant rations of water, they graciously found time to work with me, often for hours at a stretch. They are Nguyen Thi Thanh Xuan, Nguyen Trong Chinh, Ngo Nhu Trang Lieu Thi Duong, Chanh Thi Mai, Le Thi Thu, Phan Vinh Phuc, Chau Van Ri Raymond, Lam Thi Cam Thu Lien, Minh Chau Thi Tran, Mr. Thanh, and Nguyen Kim Long, whom I also thank for his superb saxophone playing.

Captain Dung Q. Nguyen of the United States Air Force, based in Misawa, Japan, reviewed much of my work, making comments and checking the spelling of Vietnamese words.

Anita Menghetti of the Lutheran Immigration and Resettlement Services, Washington, D.C., Julie Macdonald of Lutheran Immigration and Resettlement Services, New York, Michael Kocher of InterAction, Washington, D.C., Don Ranard of the Center for Applied Linguistics in Washington, D.C., and David Deas all shared with me their insights into Amerasian resettlement in the United States.

David Derthick and Gerry Collins offered their comments and assistance.

The staff of the Overstreet Memorial Library at Misawa Air Force Base in Misawa, Japan, was extremely helpful in accommodating my many requests for help in locating research materials.

My wife, Laurie Kuntz, supported this project in every way. Her ideas, suggestions, and influence are mirrored in the text. In addition, she conducted the interview that led to the oral history of Lan.

Steven DeBonis

Misawa, Japan

September 1994

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Map of Vietnam

AMERASIANS

Raymond

Nguyen Thi Hong Hanh

Minh

Tuan Den

Tung Joe Nguyen and Julie Nguyen

Manivong

My

Kerry

Nguyen Thi Ngoc Thuy

Phan Vinh Phuc

Hung

Va

Pha

Mai Linh

Vu

Nguyen Tien Dung, Mr. Loi, and Bich Dung

Loan, Be, and Dung

Phuong

Hieu

Charlie

MOTHERS AND CHILDREN

Hoa and Loan

Lan and Trung

Linh and Thu

Mai Lien and Diem

Dao Thi Mui and Thao (Patrick Henry Higgins)

Nguyen Thi Mai and Thuy

Nguyen Thi Nguyen Tuyen and Nguyen Ngoc Minh

Nguyen Thi Van and Phat

Lam Thu Cam Lien and Sophie

MOTHERS

Nguyen Thi Lang

Dung

Thanh

Anh

De

Mai

Lien

Hanh

Chau

Appendix: Changes of Province and City Names in Vietnam After 1975

Glossary

Selected Bibliography

List of Names and Terms

The guard says, “Raymond, what’s the song you singing?” I say, “I’m singing my father’s song.” He says, “Well, you know that if you singin’ that song, that mean you are the enemy.”

Raymond, an Amerasian, describing an

incident in a Vietnamese reeducation camp

She came out of that trance so common to us all and whispered in my ear: “Can you describe this?” And I said: “Yes, I can.”

Anna Akhmatova, Requiem

INTRODUCTION

August on the Bataan peninsula is the heaviest month of the monsoon. This is not a rainy season of fair days punctuated by intermittent storms, but one of weeks of drenching rain and terminal humidity. Clouds blow in from off the South China Sea and bump up against the southwestern fringe of the Zambales mountains, where they sit, like overladen ships caught on shoals, loosing their cargo on the land below. The peninsula, brown and thirsty from the remorseless sun of the Philippine summer, turns billiard-table green. Any place mold spores can grab hold and multiply, they do. Leather belts, the suede trim of track shoes, the cloth spines of hardcover books, all mildew to the color of a rice paddy.

Manivong has his most important belonging tucked safely inside his shirt against the August deluge. He carried it this way when he arrived in the Philippine Refugee Processing Center (PRPC) in Bataan a month ago. From layers of plastic and paper he fishes it out, a five-by-seven photo of a blonde, crew cut American military man wearing a pair of horn-rimmed glasses. “Father,” he exclaims proudly, pushing the photo across the table to me.

Superimposed over what would be the heart of his dad is a tiny likeness of Manivong’s Vietnamese-Khmer mother. On back of the photo is printed a Milwaukee address and inscribed in an almost childlike scrawl:

To Sapim, you are the number one girl of my life. I love you and want you so much.

Love always,

Lt. Ballman (Batman)

I look at the photo and back at Manivong. The likeness is unmistakable. Lt. Ballman was about the same age when the photo was taken as his twenty-year-old son is today.

I have seen scores of such photos in the PRPC, carried by Vietnamese Amerasians fortunate enough to own even that tiny scrap of their past. Many have had the impression that once they get to the United States, waving these snapshots will almost magically cause their fathers to appear. The real

ity, unfortunately, has been quite different.

“Before I came here, I wrote my father sixteen letters from Vietnam,” Manivong says. “I think someone received them because they were not sent back, but I never got a reply.”

In a country where postage for a single overseas letter can eat up an average day’s wages, sixteen letters represent a substantial investment. Manivong, however, is far from discouraged. He is now using the Red Cross tracing services to try and track down his dad and will continue when he gets to the United States. His chances are not good; only a tiny percentage of the Vietnamese Amerasians who have left Vietnam for America have been successful in finding their fathers.

AMERICAN RESPONSE TO AMERASIANS

The battle of Dienbienphu in 1954 marked the end of the French Colonial Era in Southeast Asia. That same year the French brought 25,000 Franco-Asian children to France and guaranteed them citizenship. The response of the United States to the thousands of half—American children left in Vietnam after its ill-fated venture there has been considerably less immediate.

In 1982, ten years after the majority of U.S. military withdrawal from Vietnam, seven years after the fall of Saigon, Congress passed the Amer-asian Immigration Act. Designed to expedite the immigration of half—American children from a host of Asian countries, it did not affect Amera-sians in Vietnam, as the United States and Vietnam had no relations. Amerasians, however, often with their immediate relatives, did begin leaving Vietnam for the states in September of that year under the auspices of the Orderly Departure Program (ODP).

In light of the horrific plight of the Vietnamese boat people, ODP was “created in 1979 to provide a safe, legal alternative to dangerous flight by boat or overland from Vietnam.”1 United States ODP officers from Bangkok travel to Ho Chi Minh City to interview applicants for resettlement in the United States. These applicants have already successfully negotiated the intricate maze of Vietnamese bureaucracy in order to obtain the prerequisite exit permit, often leaving a trail of well-greased palms in their wake.

In 1984, Secretary of State George Shultz, under the prodding of American voluntary agencies, announced the creation of a specific Amer-asian subprogram within the Orderly Departure Program. Still, the rate of Amerasian departures remained slow. In 1986, claiming that the United States had let a backlog of 25,000 applicants build up, Vietnam halted the processing of new Amerasian cases. Amerasian departures from Vietnam dropped from 1,498 in 1985 to 578 in 1986 and to 213 in 1987.2

In September of1987, the United States and Vietnam signed an agreement to expedite Amerasian emigration from Vietnam. In December of that year, Congress passed the Amerasian Homecoming Act, also known as the Mrazek Act after its sponsor, U.S. Representative Robert Mrazek. This act, which went into effect on March 21, 1988, allows for Vietnamese Amerasians and specified members of their families to enter the United States as immigrants, while at the same time granting them refugee benefits such as preentry English-as-a-Second-Language training in the Philippine Refugee Processing Center and resettlement assistance in the United States. The cumulative effect of these two events in accelerating Amerasian departures from Vietnam can be seen in the numbers: from 1982 to 1988, ODP brought approximately 11,500 Vietnamese Amerasian children and accompanying relatives out of Vietnam. Extend the period out to December of 1991 and the number jumps to 67,028.3 Also factored into this increase is the effect of a 1990 amendment to the Homecoming Act which allows both the spouses and mothers (or primary caregivers, including bona fide stepfathers) of Amerasians the right to immigrate with them to the United States. Previously Amerasians had to choose one to the exclusion of the other, a wrenching decision that often tore families apart.

AMERASIANS IN THE PHILIPPINE REFUGEE PROCESSING CENTER

My own interest lies not in numbers of departures and cases processed, but in the stories behind them. From 1982 to 1992, I worked in the Philippine Refugee Processing Center in Bataan as a supervisor in a State Department—funded educational program. This program was mandated to prepare U.S.-bound refugees for life in America. Three hundred and seventeen thousand Khmer, Lao, Hmong, Vietnamese and Amerasians passed through the center from its inception in 1980 to December of 1991, to take five-month courses in English-as-a-Second-Language (ESL), Cultural Orientation, and Work Orientation, prior to their resettlement in the United States. Amerasians and accompanying family members began trickling into the PRPC in 1985.

In most of these Amerasians, the genes of their fathers predominated; there was little of Vietnam in their looks. Freckle-faced girls, lanky young black men, blondes, red heads—one expected to hear Brooklyn rasps or southern drawls, but though many identified strongly with the American half of their parentage, they were indeed Vietnamese in language, culture, habits, in all ways but appearance. By 1988, uncorked by the Homecoming Act, this trickle had become a torrent, overwhelming many of the services set up to meet the needs of earlier populations.

Teachers in the various educational programs of the PRPC, accustomed to the deference of earlier waves of Lao, Khmer, and Vietnamese refugees, were unprepared for the young Amerasian adults now flooding their classes. By 1988, the Amerasians were no longer children. Many were already in their late teens and early twenties or beyond, and quite a few had children of their own. A significant number had been street kids or children from dysfunctional families and were arriving in the refugee camp without any accompanying relatives. Many had had little, if any, education in Vietnam, having lacked the necessary documents for admission to school, the money for tuition, or the willingness to endure the taunting that Amerasians are often subjected to from their classmates. These were the disenfranchised, shunned by their countrymen for their American blood. They lacked the support of strong family ties, and had often been forced into marginalized lives in the underbelly of Vietnamese society. For these adolescents and young adults, many accustomed to the freedom of the street, the transition to five hours a day, six days a week of school, plus two hours daily of unpaid community service, was not without its difficulties.

Disruptions and fights, once relatively rare in PRPC classrooms, now became commonplace. Drunkenness and brawling in the refugee quarters also increased substantially. Those Amerasians involved in disruptive behavior were a definite minority, generally from the more disadvantaged segments of the population, but they were highly visible. Not surprisingly, those who were unaccompanied by relatives or who had grown up on the street with little or no family supervision experienced the most problems in adapting to the structured environment of the refugee camp. Those who made the transition smoothly often expressed dismay at the behavior of the others, worrying that in the PRPC, as in Vietnam, Amerasians as a group would suffer negative stereotyping for the actions of the minority.

Counseling and recreation services were created to meet the needs of these new arrivals. Subsequent waves of Amerasians arriving at the PRPC proved a bit more restrained. Service providers were less besieged, classes ran more smoothly, and though Amerasians as a group remained problematic, the turmoil caused by the early Amerasian arrivals subsided somewhat.

AMERASIANS IN VIETNAM

Why had they opted out of the land of their mothers, the country of their birth and upbringing, for passage to the unknown land of their anonymous fathers? Most wished simply to escape discrimination and poverty. In relatively homogeneous Vietnam, foreign blood carries a strong stigma. Outsiders in the land of their birth, fatherless children in a culture where identity flows from the father, Amerasians were generally relegated to the fringe of society. These offspring of Americans were considered fair game for abuse. The taunts My lai and con lai, suffered by almost all Amerasians, and My den by those of black descent, carry stronger negative connotations then their approximate English equivalents: “Amerasian,” “half-breed,” and “black American.” Abuse often went beyond the verbal. Joe Nguyen, an Amerasian now serving in the U.S. Air Force in Japan, reports:

I remember one time, going to a movie and walk

ing home by myself at night. I was probably thirteen at that time. There was a whole bunch of kids hidden out in the bushes, and they just ran out on the street, beat me up, and took off.... That’s their game, going around, finding us, teasing us, and beating up on us, and the parents don’t do anything about it. That’s how they treat us.

Black Amerasians generally feel that they have suffered greater abuse than whites. Vietnamese negative attitudes towards blacks may have been initially shaped by their experience with the “black French,” the North African troops of France’s colonial army. Generically referred to as Ma roc, these troops acquired a terrible reputation for pillage, cruelty, and especially rape. Whatever the reason, the brunt borne by those fathered by blacks seems to have been heavier. Hoa, mother to both a black Amerasian girl and a white Amerasian boy, puts it this way:

Vietnamese say, “You go back to America, you dirty American, go back to America. You lose the war already, go back.” They say like that many times to my daughter, ‘cause she is black. My son is white, not so many problems.

Huong, a black Amerasian woman of twenty-four, concurs:

All my life people had been mean to me there [in Vietnam] because of my color. My skin is black, and my hair is curly, not like the Vietnamese, and they didn’t like that.

School was generally torment for mixed blood children. Many quit early, unable to stand the taunts of their classmates, and sometimes, even the classmate’s parents. Mai Linh, a young black Amerasian woman, explains:

Children of the Enemy

Children of the Enemy