- Home

- Steven DeBonis

Children of the Enemy Page 25

Children of the Enemy Read online

Page 25

In 1967 or 1968, Henry went back to America. He got sick there and never came back to Vietnam, but he always sent me money for Thao. You know, when my husband was in America, the police would come around looking for handouts—money, camera, radios, things like that. They think I’m rich because I have an American husband. Even after the VC came, Henry sent money until 1978, then no more money came. [Mui shows me a letter from Henry dated January 17, 1977: “I hope you receive the $50 I am sending you in this letter . . . . Maybe, in a few months, the mail will be faster. Your last letter took about 2 months to get here to me. The first letter took 97 days. “A fragment of another undated letter states: “Hello Mui and Thao, I hope you received the $50 I sent you. Can you cash the money order? I hope the mail gets better.”] Even when Henry sent money, it was not enough. I had to go out and sell soup to support my family. Then, in 1983, Henry died.

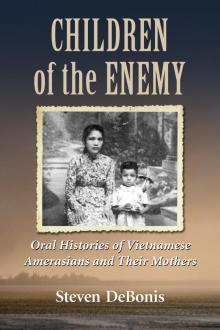

Dao Thi Mui and Thao (Patrick Henry Higgins) in Vietnam, circa 1968 (courtesy of Dao Thi Mui)

Thao and his brother in Vietnam, circa 1970 (courtesy of Dao Thi Mui)

You know, when I was thirty-seven, I died and came back to life. This is what happened. I was six months pregnant, and I hemorrhaged. I was bleeding very badly. I was taken to the hospital. My husband was in America at this time. The last thing I remember is that the French doctor said in French that they would operate, “demain a huit heures et demi” [tomorrow at eight thirty]. The next thing I remember was waking up in a room full of people lying on stretchers. I thought they were sleeping. I walked past them to the door and tried to open it, but it was locked. I knocked on the door, and some doctors and nurses opened it. They were scared when they saw me, and they ran away. I made the lay sign [palms together in Buddhist obeisance], I had no voice to speak. Finally a doctor came to me. That room was the morgue, where I had been put when I “died.” I had been dead for eleven hours and had come back to life. That is why the doctors and nurses who opened the door were so scared. They thought I was a ghost. [Mui and her son Henry are laughing at this.]

My son Minh is in America. He went there in 1975, and I don’t know where he is. My American children went to a school run by an American charity group, and they brought him to the United States before the Communists came.

Thao: We went to Catholic school for four years. Then we went to a school run by an American organization for Amerasians. We went there for two years. In February of 1975, a group of Americans came over from an agency [probably Foster Parents Plan] to bring Amerasians to America. My brother and I wanted to go. I asked if they could take my mother, but the organization refused, so I decided to stay with her while my brother went to America. We thought that he would sponsor us after he got there, but a few months later Saigon fell, and we could not leave.

Mui: We had an address for him, but it was lost, and I don’t know how to find him. All we have are these. [Mui shows me a few pictures of Minh in America; on the back of one is written “Johnny Vernon, Foster Parents Plan.” Mui believes that he was given this name by his foster parents in America.] I wrote to Foster Parents Plan, but they never answered us.

When the Communists came to Saigon in 1975, I moved to another part of the city, where I was unknown. I was afraid that if I stayed in my neighborhood, I might be denounced by a neighbor. I heard all the rumors of what the VC would do to the Amerasians, so I darkened my son’s skin with coal dust from the stove and pots and kept him inside. We had heard that in Pleiku they had killed Amerasians and their families, and we were very scared. We stayed inside for a week.

Under the Communists, the new regime, we had to report to the work council. My son had to stay about ten days. He was very young at this time, maybe ten or eleven.

Thao: They made me clean the prison, clean their office, wash their clothes. I was very polite. I said, “Yes sir, yes sir,” and I did what they asked. In a week they let me go home. There were other Amerasians there. The ones who did not speak politely they kept longer.

Mui: I brought rice to him twice a day. After I gave him the rice, I would cry and cry on the way home, right in the street. Why should they keep my son? He is only eleven, what is his crime?

Thao: After the Communists came, I couldn’t go to school anymore. I didn’t have the right ID. I didn’t even like to go out anymore, people made fun of me. I mostly stayed inside.

Mui: The work council called me and told me that I would have to go to the New Economic Zone. I didn’t want to go. I told them I was sick, and they sent me to a Communist doctor. Before I went to see him, I sold four bracelets, some of gold and some with blue stones. I took the money, stuck it in an envelope, and put it inside my clothes. When my turn came to see the doctor, I gave him the envelope and asked him to write me a note. He wrote that I had an enlarged heart, and this kept me and my family from going to the NEZ.

The note, however, did not exempt me from forced labor. The new government made us work for them for no wages. They called me and I had to go. They sent me to Hoc Mon, which was about thirty kilometers from Saigon. I had to dig canals for the Communists. The women are the ones who do the digging. I was chest deep in water all day, scooping up earth and piling it on the banks. I had to get up at four in the morning, and they drove me in a bus to the site. We worked until seven P.M., then they drove me back to Saigon. For lunch we had rice and rotten meat. It was worse than prison. From Hoc Mon they sent us to Cu Chi and then to Le Minh Xuan, the place named after the Communist hero. We got no pay, it’s all forced labor. To get money for my family, I sold gasoline on the street on the weekend.

I worked for several months. Then finally I bribed someone at the work council and they let me go. I had gotten malaria on the job. I went to the Communist clinic, and they gave me some orange medicine. It didn’t do anything, so I had to go to the market and spend money on malaria pills, and these cured me.

In 1982 we applied to leave Vietnam through the Orderly Departure Program and waited and waited. We did not know the way to bribe the Communists. Finally, in 1989 my daughter got to know someone who was a friend of a member of the application committee. He arranged the bribe, and we paid two bars of gold. Even with the bribe, we waited three years because we had to change our documents. We wanted to take my daughter, but she was denied. Then Thao got married, and we had to make documents for his wife. He and his wife have three children. The last one, a girl, was born about a month before we left Vietnam. We had to leave her behind. We couldn’t get her included on the documents. We will try to bring her over once we get to America.

Thao: Before we were accepted by ODP, I tried to escape Vietnam four times, but I failed each time. The first time I tried to escape with my wife and one child and my brother-in-law. I only had one child then.

We had made arrangements in Saigon, and our connection took us to Ha Tien in the south [on the Cambodian border] and put us on a small boat. We were supposed to meet a big boat which would take us to Thailand. The big boat didn’t show, so the captain took us to an island and asked us to wait there while he located the big boat then he would come back. So he dropped us off on a small island, completely uninhabited.

Well, the whole thing was a setup, they never came back. The island was inside Cambodia, and some Cambodian fishermen came by to fish off the island. They could speak Vietnamese. I told them what had happened to us. They were very kind. They took us to their home on another island, and we stayed with them for about twenty days. When they went to the Cambodian mainland, they took us with them. Their island was a long way off the coast. It took many hours for us to get to the mainland.

The fishermen took us to the bus station and loaned us some money, and we got on a bus for Pnom Penh. In Pnom Penh there were many Vietnamese vendors in the market. I didn’t want any one to know why I was in Cambodia, so I approached one and said, “I have been visiting my relatives here and I am trying to get back to Vietnam, but I am lost.” They directed me to a boat on the Mekong River, which took us to the Cao Lanh district in Dong Thap province. [I as

ked Thao why, once he was in Cambodia, he didn’t continue on to Thailand. He said that he had no guide and was afraid to continue without one. My interpreter concurred, saying that police in Cambodia are very aware that many Vietnamese use that country as a conduit of escape into Thailand, and it is very risky to try it without a guide.]

When I got back to Ho Chi Minh City, my family told me that the boat owner had come by to collect the money for the trip, saying that we had reached Thailand safely. But before we had left, we devised a coded message which I would telegraph once we reached Thailand, to let my mother know that we had gotten there. The message was simply, “We reached the island safely.” Since the boatman didn’t know the message, he didn’t get the money.

When I got back to Vietnam, I went to ODP to check on the progress of my application. They told me that my application was lost. At that time people weren’t moving. Everything seemed stalled. I made the ODP papers again, but I had to think of escape.

I arranged to try and flee Vietnam again through a Saigon contact. We took a bus to Vinh Chau, a few hundred kilometers south of Saigon. My wife had had another child since the last escape try, and she was with me along with my two kids. We had paid four gold rings as a down payment. If we escaped, the plan again was to send a coded telegram to my mother and she would turn over four bars of gold.

We waited two days in a hotel there. My contact used his documents to get us a room. After two days they took us to a small thatch hut by the sea, where we were supposed to board the boat. The police noticed that there were people in that small town whom they had not seen before. Since it is a seaside town and people have escaped from Vietnam from there, they are always on the lookout. They came into the hut, demanded our documents and arrested us. Then they took us to jail in Vinh Chau.

Mui, Thao, and his sons

That same night my wife, who was having her period, began to bleed very heavily, and passed out. They sent her to the hospital, and after three days she was released and her and the kids were sent home.

I was not that lucky. They kept me two months in Vinh Chau jail, and then I was transferred to Long Tuyen prison in Can Tho province. There was no trial, or anything like that, and I was never told when I might be released. The police didn’t even inform my family that I was sent to Long Tuyen. My family came down from Saigon to Vinh Chau to visit me, and only then did the guard tell them that I had been transferred.

They stuck me in a cell with about sixteen other men. It’s unbearably hot there, like a furnace. There was a hole in the floor for a toilet, and the place stunk. We were never let out. We just stayed there all day and night.

The cells are tiny and crowded. There’s really no room to lie down and sleep. People would roll over in their sleep, knock into another person, and a fight would start. This happened all the time. Or if one person had food and another didn’t, there might be a fight over that. Sixteen people were in a small space; every day there were fights. If they got too bloody, the guards would come in and take the prisoners involved to other cells. But a few days later, they’d bring them back, and the fights would start all over again. The guards don’t care at all what happens in the cell. They just let the dai bang, the chief prisoner, and the other inmates handle the problems.

When I got into the prison, the dai bang saw that I was Amerasian, and he asked why I had been arrested. I told him that I was visiting relatives in Bac Lieu and I had no documents, so the police arrested me. If I had told the dai bang that I was trying to escape Vietnam, he would have figured that I had money and would have strip searched me to look for it. He was a big fat guy with tattoos and had been in prison a long time. He didn’t bother me much, I stayed out of trouble. The worst he did was force me to lie near the stinking toilet.

There were many Thais in Long Tuyen, mostly fishermen caught in Vietnamese waters and pulled in by the police. They more or less roamed around the grounds, not caged up like us. They weren’t given rations, and so they begged for food from the Vietnamese. They are very aggressive, and there were a lot of them. I was afraid of them, even the guards were wary of them.

The police questioned me: “What was I doing in that hut by the sea?” I told them that I was just visiting relatives, that the man in the hut was my uncle. I was caught in the hut and not on the sea, so I stuck to my story. After a month or so, they let me go. If I had been caught on the boat, I would have been in jail much longer.

My third escape attempt I was set up again, I believe, though my neighbor’s son made it to Indonesia on the boat that was also supposed to take my family. I paid five gold rings in advance to get on that boat. We waited in Vung Tau, and the boatman was supposed to contact me. I waited for a day and finally got suspicious, so I went to talk to the landlord of the house. He said that the boat had already left. As I said, my neighbor’s son made it to Indonesia on that boat, and his family received a letter from him. He said that the boatman took him to the boat to help make arrangements for food and water, but when he got there, they sailed off unexpectedly, and the boatman wouldn’t let him go back to get me. Why the boat left without me, I don’t know. Anyway, we lost five gold rings on that deal. [Stories of passengers being left behind during boat escapes are far from rare. Many times the boat pulls out just ahead of capture by the police. People and cargo are often left behind in the scramble.]

We tried one more time. This time we got on a boat in Ba Ria, near Vung Tau. The police saw us, and the captain beached the boat. We ran away, and the police didn’t get us.

My father left us a lot of money when he died in 1983; but it is in America, and we have not been able to get any of it. We received a letter from my father’s lawyer, telling us that we had inherited the money, but that it couldn’t be sent out of the United States. So all these years we have had that money in the bank in Florida, but we were very poor. Here we have no money.

My mother has a problem with low blood pressure. Every week she has to go to the doctor. Last week she fainted and was brought to the hospital and they had to give her oxygen. The doctors here do not treat refugees kindly. They are often nasty to us, so it is unpleasant to use the hospital. [When Thao says this, my interpreters nod in agreement.] One of the doctors said that my mother may not live long enough to see America. I worry about this, and I wish we could go to America right now.

My mother is very weak. She needs good food, but we have no money. I wrote to my father’s lawyer, asking if there is any way that we could get some money here from my father’s inheritance, but I have not gotten a reply. I have been selling our clothes, piece by piece, to buy food. I have almost nothing left.

When I get to America, I hope to find work as a tailor. That’s what I did in Vietnam. Eventually, I’d like to study and become an army doctor, like my father was. I will put my father’s inheritance in the bank and use part of it to help orphans in Vietnam. And maybe I will have to use some to put my mother in a home. I don’t want to do this, but I learned in Cultural Orientation class about old age homes, and my cousin from California wrote me that that’s what Americans do with old people.

My cousin in California, she is sponsoring us now, but I hope that my father’s lawyer can sponsor us instead. He is in Florida, and that’s where I want to go. That’s where my father’s grave is.

Postscript: I remained in contact with Mui and Thao through August of 1992, when I left the PRPC. Mui’s health had stabilized, though she was easily prone to fatigue. At Mui’s request, I wrote a letter to Foster Parents Plan, the organization which she says brought her son Minh to the United States in 1975. We hoped to get some information which could aid her in locating him. In May, I received a reply from a representative of Childreach Sponsorship, a program of Plan International USA (formerly Foster Parents Plan). It stated: “I asked some employees who worked here during the year 1975, if it were possible that our organization brought some of the Amerasian children to the United States. I was told that it was possible but that we would not have any records in wh

ich to verify that information. I’m very sorry that I was unable to help you.”

A letter also came in from the Pearl S. Buck Foundation, Inc. They have a data base on Vietnamese Amerasians who are searching for family members. Childreach had forwarded our inquiry to them. Unfortunately, Minh’s name did not appear on their database. Their representative suggested Mui contact the American Red Cross and the Citizen’s Consular Service of the Department of State. Mui says she will follow these leads when she gets to the United States.

Nguyen Thi Mai and Thuy

“The VC, they killed my mother.”

Despite political and military developments indicating the contrary, many South Vietnamese never believed their country would fall to the north. Mai is one of the many Vietnamese women married to Americans who waited too long to try to leave Vietnam. Mai’s husband had sent her and their daughter Thuy one-way tickets to the United States in the spring of 1975. By that time, however, the government in South Vietnam was crumbling. Chaos ruled at the airports, and Mai and Thuy were stuck.

I first met Mai when she was a student in an ESL class in which I was assisting. Weeks later I ran into her near her billet in neighborhood two of the PRPC. It was about 6 P.M., and the camp water, which operates only a few hours a day had been turned on. Refugees were waiting in line with buckets to gather the evening’s ration. Women sudsed up little children by the side of the water tanks that supplied the neighborhood, and teenage girls squatted beside plastic buckets of laundry. The early evening break in the intense March heat and the turning on of the water, which had been erratic of late, had buoyed everyone’s spirits.

Children of the Enemy

Children of the Enemy