- Home

- Steven DeBonis

Children of the Enemy Page 11

Children of the Enemy Read online

Page 11

In Vietnam I worked very hard and I could never go to school. Here, in the PRPC, I can study English, and the work is not very hard, so it is better here than in Vietnam, but still I am anxious to go to America. I want to find my father, I will be so happy if I can see him. I hope he can help me to continue studying. We have many things to talk about.

Nguyen Thi Ngoc Thuy

“All children of Americans were considered children of the enemy.”

At first glance, I take Thuy for Cambodian. It is her dusky complexion and the full turn of her cheeks. She is sitting outside the neighborhood five market, a black umbrella shielding her from the sun. Spread in front of her on a plastic tarp is a bewildering array of goods for sale: old Walkmans, used clothing, English-Vietnamese dictionaries, ancient clothes irons that run on charcoal embers.

I try out a few words of my limited Khmer on her, and she answers in same. After a few sentences, we both run out of language, and Thuy laughingly breaks into English.

Thuy did spend a short time in Cambodia, where she picked up the few Khmer phrases she used in answering me, but her copper-toned skin and thick wavy hair come from her black GI father. Her mother is Vietnamese. I was not the first to mistake Thuy’s ethnicity. In Cambodia, even the Khmer people thought she was one of them.

Although she hardly spent a day in school in Vietnam, Thuy has acquired some skill in the English language. She is quite outgoing and is not afraid to make a mistake. Although we generally spoke through an interpreter, she would try to understand my questions in English and take a crack at answering them directly. When the language became too complex, she would turn to the translator for assistance.

She is in the PRPC with her husband and three children. The youngest, she says, she found abandoned on a bridge in Ho Chi Minh City. Thuy, now thirty, was herself an abandoned child, left with an often callous caretaker when her mother married a Vietnamese man. After enduring years of ill treatment, she left for Saigon, where she spent most of her life, living on the street.

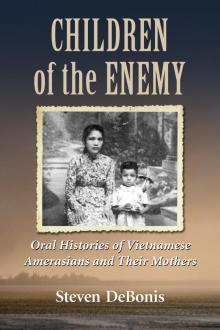

One evening, as we sit in her billet, Thuy hands me a tiny black and white photo. At five years old, her slender child’s frame belies the stocky lady she would become. Her mother sits by her, clad in the traditional Vietnamese ao dai. The woman and the child both stare stiffly at the camera. The photo, sepia from age, has the antique quality of heirloom pictures one sees in lockets or in tiny filigreed silver frames. Thuy recounts how, after the fall of South Vietnam, she traced her mother to a village in Thuan Hai province. Despite a happy beginning, their reunion ended in conflict, brought on by the refusal of her mother’s husband to accept her. In spite of Thuy’s pain at this second rejection, the two women reunited and made amends just weeks before Thuy left Vietnam in December of 1991. “Even though she abandoned me,” Thuy says, “even with all the problems that we had, she is still my mother.”

I WAS BORN in Phan Thiet, in Thuan Hai province. I never saw my father. My mother told me that he went to America when she was three months pregnant. She said my father’s name was Mickey, and she was washing dishes at a bar where she met him. That’s all I know about him.

When I was little, my mother washed dishes at Minh Mang restaurant near Phan Thiet. After that she worked as a vendor. She left me with a lady, a sort of baby-sitter, who watched me while she went out to earn money.

When I was still young, maybe seven or eight years old, my mother gave me away to the baby-sitter. That lady became like my stepmother. She told me that my grandmother was angry at my mother for marrying a foreigner, my father, and that’s why she left me. My mother came to visit me, but only two times. Then she didn’t come no more. After that, she married a Vietnamese, and she didn’t want me anymore. It was many years before I saw her again.

I was very sad when she left, but I was confused. I was young when I went to live with my stepfamily, and I didn’t really understand if they were my real family or not. Some neighbors told me that I was adopted, but I could not understand.

I never went to school. My stepmother had three children, and she made me take care of them. I received little affection from that family. My stepfather didn’t abuse me, but my stepmother tormented me. She hated me because I was black. She thought I was dumb. She called me stupid, and she beat me. One time she hung me upside down. When I was about as old as this girl [Thuy points to an eight-year-old child], she made me strip to the skin and stand outside in the hot sun. Sometimes I would hide under the bed and wait until she left before I came out to eat.

She was so unkind. One day a beggar passed my house, and I gave her a can of rice. That made my stepmother furious. Another time I shared some food with a neighbor. My stepmother beat me for that.

We lived in Phan Thiet town, near the sea, in a big house with a well outside. My stepfather was a fisherman. I worked by carrying the fish and drying it in the sun. Then my stepmother took them to sell.

My stepfather died when I was about ten. He dove under the sea to spear fish. There was a compressor on the boat, with a hose that supplied him with air underwater. The compressor broke, and he could not get air. He never came up.

Thuy at five years old with her mother (courtesy of Nguyen Thi Ngoc Thuy)

My stepmother hired many men to search for the body of her husband. They tried for one week, but they couldn’t find him. The family was Buddhist, but there was no ceremony because there was no body.

When I was twelve, I heard from a neighbor that my real mother was living in Saigon, so I left my stepmother’s house and got on a bus for Saigon. I had no money, so I tried to avoid paying the fare by means of various tricks. For example, when they came to collect my fare, I would point to someone in the back of the bus and say that she was my mother and would pay for me. When this didn’t work, I would get off the bus and wait for another and try the same thing. In this way, I boarded several buses and finally made my way to Saigon. Of course, I didn’t find my mother.

I went over to Ba Chieu market and begged for scraps. I slept at the market with some other beggars. After about a week, I went over to Quach Thi Trang Park and began shining shoes. I worked with a group of Amerasians—two boys and four girls, all black, like me. They have all gone to America already. We slept in the bus station, or if it was not raining, we sometimes slept in the park. You know at that time, the black and white Amerasian stayed separately, not like now. Now they mix very freely, but then white Amerasians didn’t want to make friends with me.

This group taught me how to shine shoes. It’s not difficult. I tell the customer to put his foot up on the shoeshine box, I put on some polish. I have a long cloth. I hold an end of the cloth in each hand, and then I buff the shoe, like this. [Thuy demonstrates a vigorous shoeshine motion.] I got three dong for a pair of shoes. Some days I would do five pairs, other days only two pairs. We pooled our money in the group, that’s how we lived. I also worked as a dishwasher in a boardinghouse and as a newspaper seller.

I would take a bath and wash my clothes at the public faucet. One time, I washed my clothes and hung them up on a fence near a gas station. I sat down to keep my eye on them. But I got sleepy, and as much as I tried, I couldn’t help dozing off. When I woke up, my clothes weren’t there. I ran up and down the street looking for them, but it was too late. They were gone. [Thuy laughs at the memory.]

There were gangs on the street. Sometimes bad things would happen, but nobody bothered me. After I lived on the street a while, I knew my way around. I think maybe I had a look about me, and people left me alone.

When I was fourteen, the Communists came to Saigon. I was selling newspapers on Le Lai Street at that time. All the Americans had left Saigon. All children of Americans were considered children of the enemy. We could not find work or a place to live. It was very difficult. I was afraid, and I felt lonely. I began to think, even though I had been mistreated when I was a girl in Phan Thiet, wasn’t it my homeland? So I got on a bus and went back there, back to my home province, Phan Thiet.

When I got to my

stepmother’s house, I saw that there were new owners. The neighbors told me that my stepmother had died of hemorrhagic fever. I was sad, despite the way she had treated me. Some neighbors told me that my real mother was living in a small village, not too far from Phan Thiet. I took a bus there. It is a poor farming village. When I found my mother’s house, we recognized each other immediately. It was almost like telepathy. We just held each other and cried, overcome with emotion. We were so happy that we could not talk.

I stayed in my mother’s house for two days. It is a small thatch hut with a dirt floor, like most of the houses in the village. After that, she took me to a friend’s house, where I waited while my mother discussed the situation with her husband. I didn’t think he was very happy that I had come.

After a week I moved back to my mother’s house. I stayed there for three months. We got along well for the first month, but after that my mother and her husband started arguing. He didn’t want me to live in their house, and he always walked around with a cold face. Finally, my mother and I had an argument. She told me, “You are stubborn, because of your mixed blood.” I became angry. I told her, “If I were white and beautiful, you would never have left me.” My mother didn’t say anything, she just cried. Soon after that I left my mother’s house. I just slipped out without telling anyone. I did not want to disturb the harmony of her house or disrupt her marriage.

When I back to Saigon, I was afraid that the government would send me to the New Economic Zone. Some friends of mine heard that it was easy to make money in Cambodia, so they decided to go there. I went along with them. We crossed the border at Dinh Xuong village, Dong Thap province. Because I was black, they didn’t question me. They thought that I was Khmer from one of the border villages. These people often cross back and forth, so I walked right across. My Vietnamese friends had to sneak around, but I walked right through because I’m black like a Khmer.

We took the bus to Prey Veng city. I set up a stand near the Buddhist temple frying bananas and selling them. At night, I slept at the market. In a few months, I began to do general buying and selling. I bought from Vietnamese and sold to Vietnamese and Khmer.

The Khmer liked me better than the other Vietnamese because my color was more like theirs. They would say that my skin is like a Khmer, but my face is different. I went to sell at the market with Vietnamese who were born in Cambodia and spoke the language fluently, but the people used to think that I was the Cambodian because of my color, and I was the one they would talk to. This was different than Vietnam, where they hate my black skin.

Cambodia was much better for business than Vietnam. There were not so many rules and regulations, and the Khmer people are very kind. Many Vietnamese do business in the market, and nobody bothers them. I always was honest with the Khmer, and they were good to me in return. Many times they invited me to their homes, to eat together.

I left Cambodia, just when many Vietnamese soldiers were coming in. A lot of Vietnamese were leaving at this time, and there were stories of terrible things happening to the Khmer, but especially to the Vietnamese. I was afraid that Pol Pot would kill me. It was said that the Khmer Rouge cut Khmer into three pieces, but mutilated Vietnamese into seven pieces. Why the difference, I don’t know. There were Khmer Rouge in the hills, and even in the town. Some people in town, you don’t know that they are secretly Khmer Rouge, and at night they kill you.

When I got back to Saigon from Cambodia, I started sleeping on Le Lai Street, by the Le Lai Restaurant. There were many people sleeping out there, many Amerasians. One day, the owner of the restaurant, a Chinese guy, asked me if I wanted a job. He gave me food and clothing and a place to stay, and he said he would protect me if I had trouble on the street. Sometimes he let me sleep in the restaurant. Sometimes I worked in the day and slept out on the street. I worked there for a year, I worked very hard. One night the owner came to me when I was sleeping. He told me that if I didn’t sleep with him, he would throw me out on the street again. He was around thirty, I was only about seventeen. I had nothing, so what could I do? I let him have his way [Thu.y is weeping at the memory]. I hated it, but what choice did I have? After a few months, I became pregnant. When I was three months pregnant, his wife confronted me and put me out.

So I was seventeen and pregnant, no home. I just wandered around, finding work as a dishwasher in little food stalls, sleeping on the street.

When the time came to have my baby, I couldn’t get to the hospital. I gave birth on the street, right on the sidewalk. Some strangers, some passersby helped me. After the birth, I kneeled on the street with my baby in my pants, the cord still attached. I was too weak to hold the baby. I tried to get a taxi to take me to the hospital, but none would stop. Finally, after two hours, one did, and I got to the hospital. My baby was healthy, but my legs, my knees, have always given me trouble since then, pain from the knees to the ankle.

After my baby was born, I started selling ice tea in Quach Thi Trang Park near Ben Thanh market. One man stopped at my stand and bought ice tea from me every day, on his way to hairdressing school. He became my boyfriend, and now he is my husband. We lived together on the street.

At this time, the VC came and rounded up all the vendors. They told us that if we didn’t voluntarily go to the New Economic Zones, they would send us there. They told us that if we went voluntarily, there would be a house and a job for us. That’s what they said. So we made a paper to “voluntarily” go to the New Economic Zone.

Nguyen Thi Ngoc Thuy, husband and friends outside her “home” on the sidewalk in Vietnam

We had no choice over where to go. They just sent us to Cay Truong 2 in Song Be province. We lived on newly cleared land on the edge of the jungle and mountains.

We built a hut out of palm thatch, and that’s where we stayed. I cleared land, dug holes, planted rice and vegetables. All labor, all hard. We planted manioc. We didn’t get paid for our work, but we sold part of the vegetables we grew for a little cash.

I made a little stove out of three stones. They gave us some rice a few times a week. I had to borrow pots to cook in. I was voted in as a leader for distribution of goods, but there wasn’t much to distribute. Rice was lacking, we had to eat manioc.

Some of the cadres there teased me. “You are American,” they said. “Why don’t you go back to America?” I said, “I planted the rice, now I want to harvest.” But I never did. It was too hard to live there. It was difficult to get water, food was scarce. One day we went to the market in a nearby village, as if we were going to buy supplies. When we got there, we boarded a bus for Saigon.

We got to Saigon and just continued to live on the street, wandering around. I sold fruits like mango and banana on the street in front of Independence Palace. My husband couldn’t find a job as a hairdresser, but he got some work as a bricklayer. We had no ID card, no household certificate, so nobody could rent a house to us. My whole life in Saigon, I stayed on the street. [Thuy shows me a picture of herself, her husband and some other people sitting on mats on the sidewalk. There are some makeshift enclosures in the background. Thuy points to one . . . “That’s my house.”]

Thuy and her son

Sometimes it would rain, the water would come inside. We would have to stand up and hold the babies. My oldest one would stand under an overhang in front of a house. This is how we lived.

At times the police would come and tell me to move my things. Where could I go? But if I didn’t move them, they just take them all away and I never see them again, so I have to move.

My husband never knew his real family, he was an orphan. Many people tell him that he looks French, but since he never knew his parents, he doesn’t know for sure. He was raised by a stepfamily in Dong Thap province.

In 1988 I was pregnant, and my husband wanted to visit his family. I went with him. They hated me, they wouldn’t talk to me. They said to my husband, “Why did you get a black wife? You are white.”

It’s worse in Vietnam for blacks than whites. The Vi

etnamese hate blacks. That’s why I don’t want to live with Vietnamese in America. Vietnamese don’t like me. They always make me feel inferior. Even when I was a girl, seven or eight, people didn’t want to make friends with me. That’s when I knew I was not the same as them.

I applied for the Orderly Departure Program in August of 1989, and in December of ’91 I got here. I never paid any bribes, I was very lucky. Many people have to pay bribes, sometimes more than $1000. Just before we left for the Philippines, we stayed at the Amerasian center in Dam Sen. I went back to Phan Thiet province and got my mother, and I brought her to Saigon. She stayed with us for a week. Even though she abandoned me, even with all the problems that we had, she is still my mother. That’s what I told her. [Thuy shows me a color shot of herself with her husband and daughter, standing in back of her mother, a seated fiftyish woman. Everyone seems happy.]

I hope that my husband can get a job in the United States, maybe as a hairdresser. Maybe I can be a laundry woman or do ironing, something like that. What I would really like is to be a saleslady—sell watches and cassette players, something like that. I just want to support my kids. I want my children to go to school. But I am worried. We learned that in America everything is run by machine. How can I work? I never went to school.

Postscript: A week before her departure for the States, I visit Thuy in her billet in neighborhood six. She is rummaging through a cardboard box for a book of photos. When she locates it, she lays it on the table for me to peruse and walks off to start a pot of rice for dinner.

Children of the Enemy

Children of the Enemy